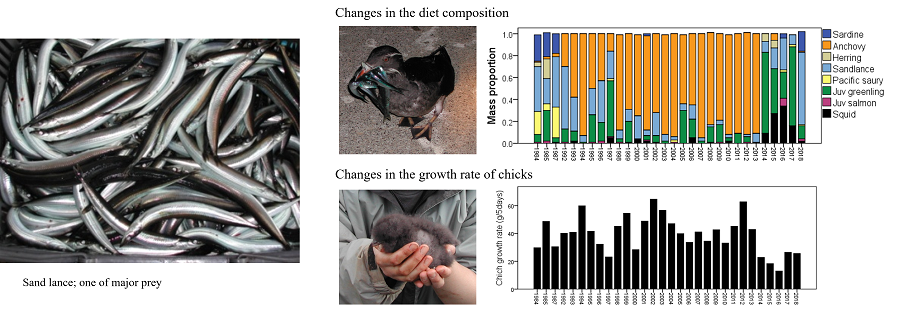

Seabirds can be a good indicator of the changes in global marine ecosystems. Surveys of seabirds are easier and they cost much less than boat surveys. Seabirds are marine top predators ranging widely and thus can be an integrated and useful indicator of a broad range of ecosystems. Rhinoceros Auklet is a species that breeds at mid-and high latitudes in the North Pacific, burrowing and nesting on isolated islands, diving to 70 m depth, and feeding on a variety of forage fish. Parents return to the islands at night. We have monitored food and chick growth for more than 30 years on Teuri Island located in the Sea of Japan in Hokkaido. We found that the chicks grew better when they were fed with sardines and sand lance in the cold period in the 1980s and anchovy during the warm period in the 1990s. However, after 2014, juvenile greenling was the main prey species, and the chick growth and fledging success were poor. These timings of prey-switching have been associated with decadal-scale climate change, i.e. regime shifts. After 2018, the birds began to eat the sand lance again: indicating the start of the cold regime or may be not. Thus our study indicates that marine birds may signal a major shift in marine ecosystems in advance.