Matter movement - it's important to think about size ~

The chemical parameters measured in oceanographic observations are elements related to biological activity. Elements involved in or close to living organisms are called bioelements or biophilic elements. The oceanic distribution of pro-living elements is also broadly classified according to water mass classification. This is because water masses that sink at a certain location travel through the middle and deep layers of the ocean over a long period, and the matter contained in the water masses continues to travel with them, changing form as they do so.

However, only substances that are dissolved in seawater (i.e., dissolved matter) or have the same density as seawater (i.e., floating or suspended particles) can continue their journey with the water mass. If a matter becomes larger than the density of seawater, it will gravitationally fall and disappear from the water mass. So what is the matter that gravitationally falls in seawater (i.e., sedimentation particles)?

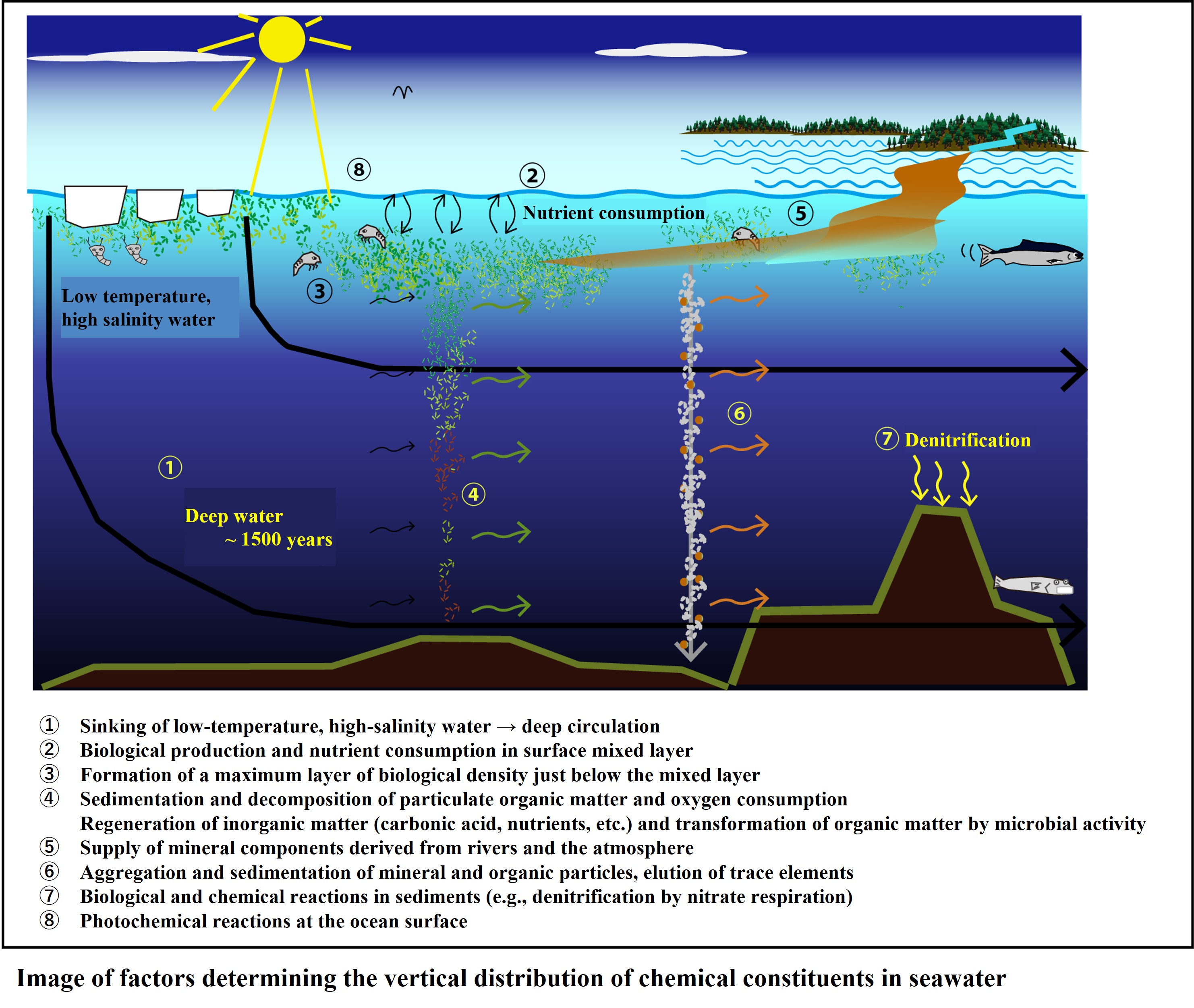

The first thing that comes to mind would be animal carcasses and feces. These particles are produced primarily in the surface layers of the ocean and settle at a relatively fast rate. Below is a pictorial representation of the factors that determine the vertical distribution of chemical constituents in seawater. This chapter will help you to get a concrete image of the factors.

Most of the particles in surface seawater are thought to be phytoplankton. They change their shape and sediment, decomposing in the process. Other particles include mineral particles that fall from the sky (yellow sand particles in the North Pacific), which are small (a few µm) and do not have sufficient sedimentation rate on their own. They are thought to sediment in the ocean by attaching to other particles (e.g., phytoplankton). To begin with, phytoplankton lives suspended in water, so it has a density almost equal to the density of seawater and is difficult to sediment. After the phytoplankton die and the various organic particles come together to form an aggregate, they may gradually begin to sediment.

Organic matter in suspended and sedimentary particles is used as food for microorganisms, leading to the decomposition and mineralization of organic matter. When the size of the organic matter is reduced to the limit, it is gasified and released into the atmosphere.

Considering the above, you can imagine that the biophilic elements (carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, iron, etc.) show quite complex behavior in seawater. The previous statement that "the distribution of chemical parameters is also broadly classified by water mass category" only means that "the distribution of chemical parameters changes abruptly at the boundary of a certain water mass". To consider these factors, one must have a three-dimensional and temporal picture of the movement and mixing of water masses, the suspension and sedimentation of particles, and the formation and decomposition of dissolved and particulate matter.

Since organic matter is responsible for mass transport in seawater, Chapter 2.1 deals with "Organic Matter in the Ocean".