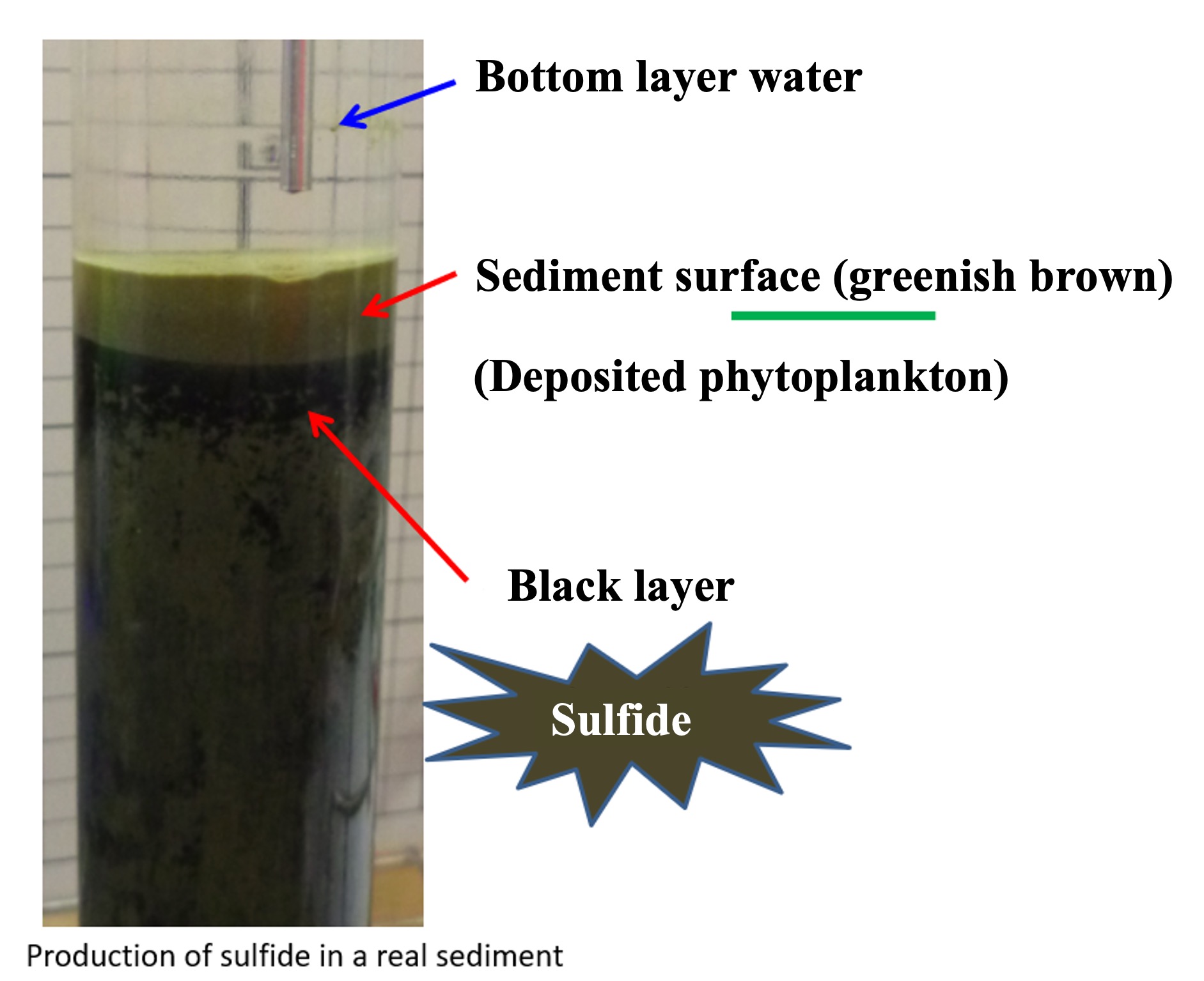

The photograph below shows a core (cylindrical) sample of marine sediment from 300 m off the coast of Hokkaido, Japan, sealed in a glass tube for storage. The surface layer of the sediment, about 1 cm thick, is greenish brown in color. This is due to the abundance of phytoplankton-derived organic particles produced in the surface layer. A black layer can be seen directly below this layer. When this black sediment was collected and hydrochloric acid was added, bubbles were generated. When this gas was passed through a lead chloride (PbCl2) hydrogen sulfide detector tube, high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide were observed.

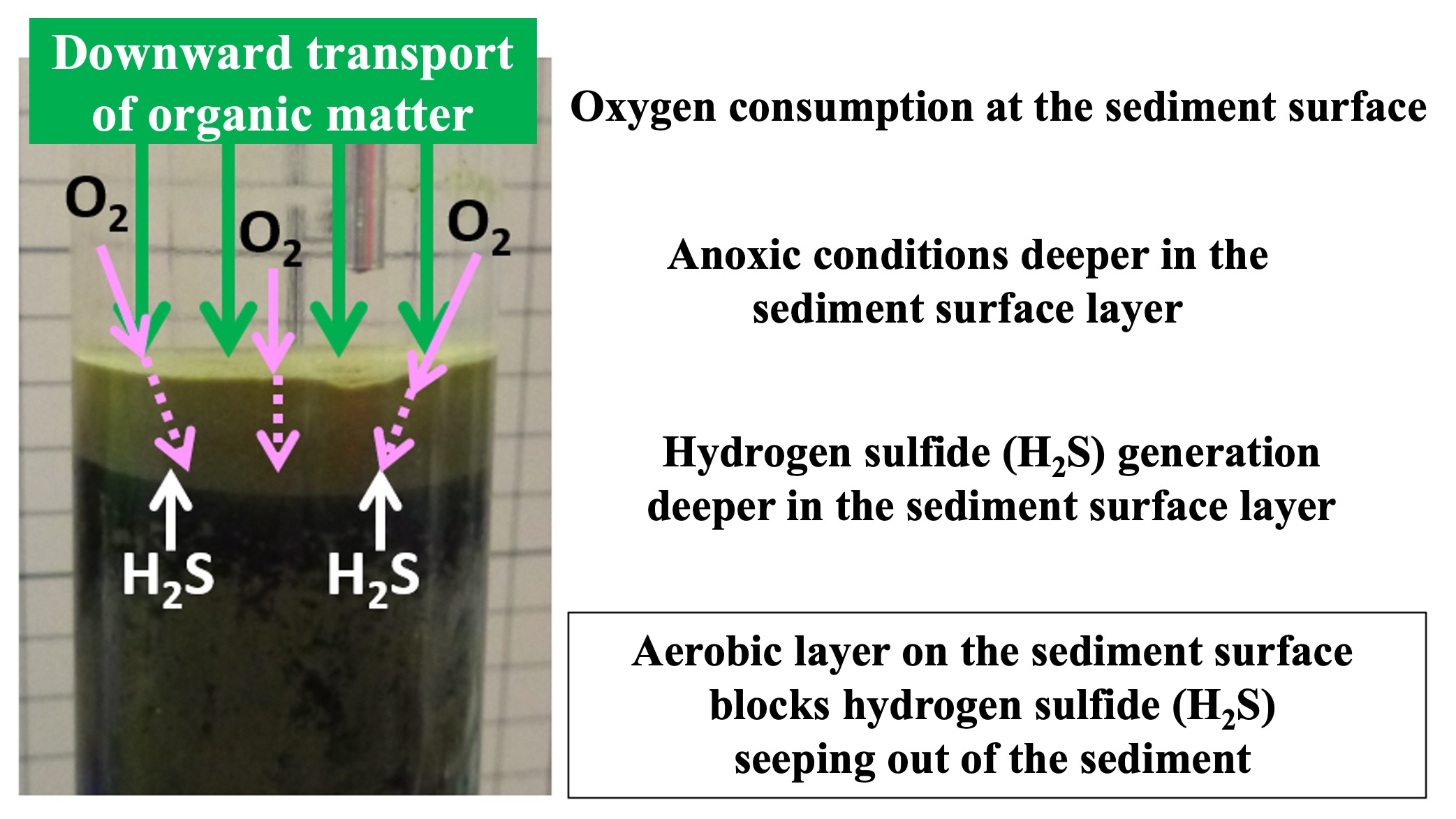

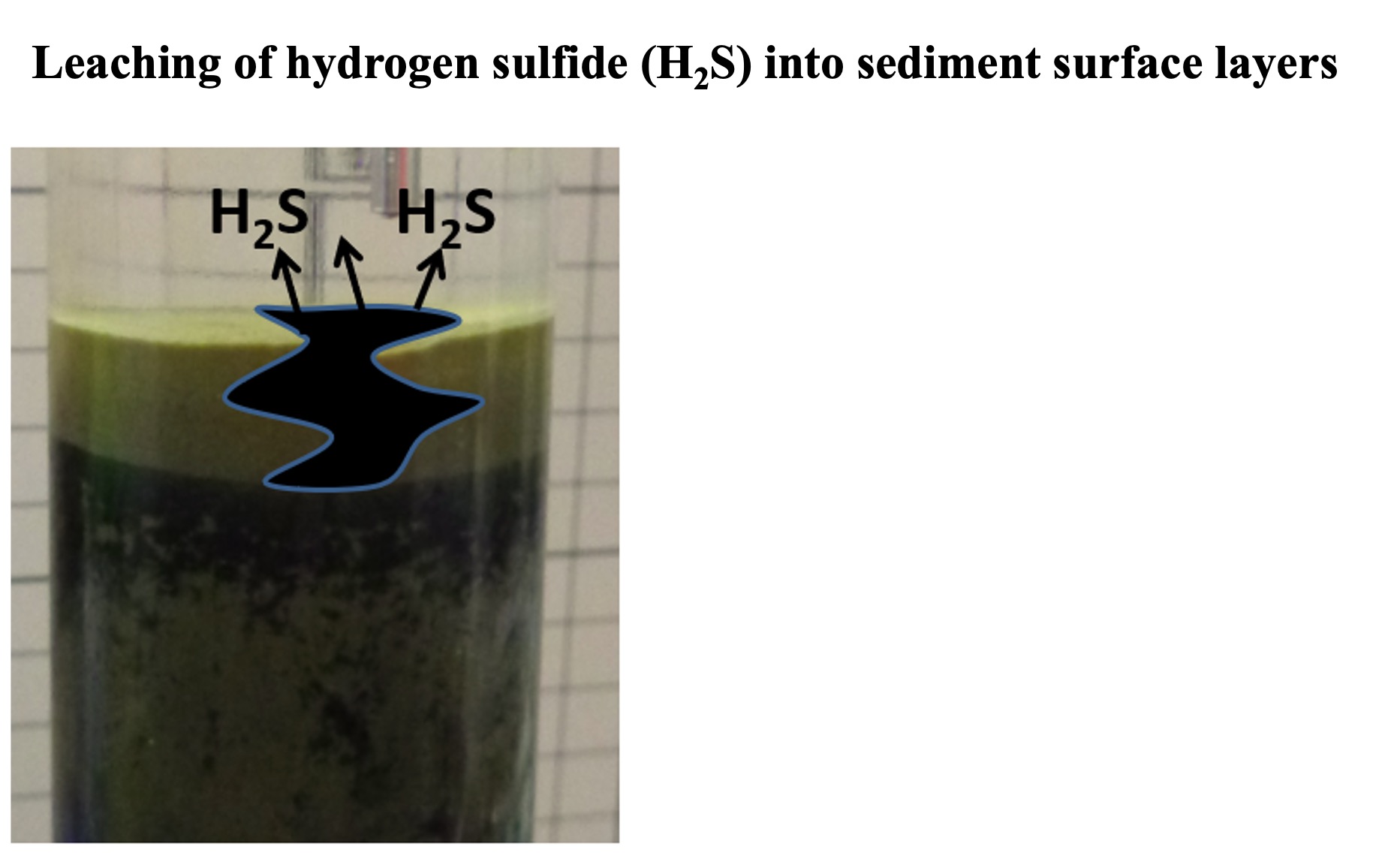

Why is it that the black sedimentary layer, which generates hydrogen sulfide, does not reach the surface? Bottom seawater contains oxygen, which is supplied to the sediment surface. In the sediment surface layer, respiring oxygen microorganisms decompose fresh organic particles by respiration. This oxygenated sediment surface layer blocks the leaching of hydrogen sulfide from below. This is because hydrogen sulfide is relatively quickly oxidized back to sulfate ions when it encounters oxygen. (This sulfide oxidation is also believed to proceed quickly by bacterial action.)

Since the Hokkaido coast faces the open ocean, the bottom seawater is supplied with oxygen on a steady basis, so hydrogen sulfide does not leach to the sediment surface. In inland bays such as Tokyo Bay, where the supply of organic particles is significant, hydrogen sulfide may leach to the sediment surface.

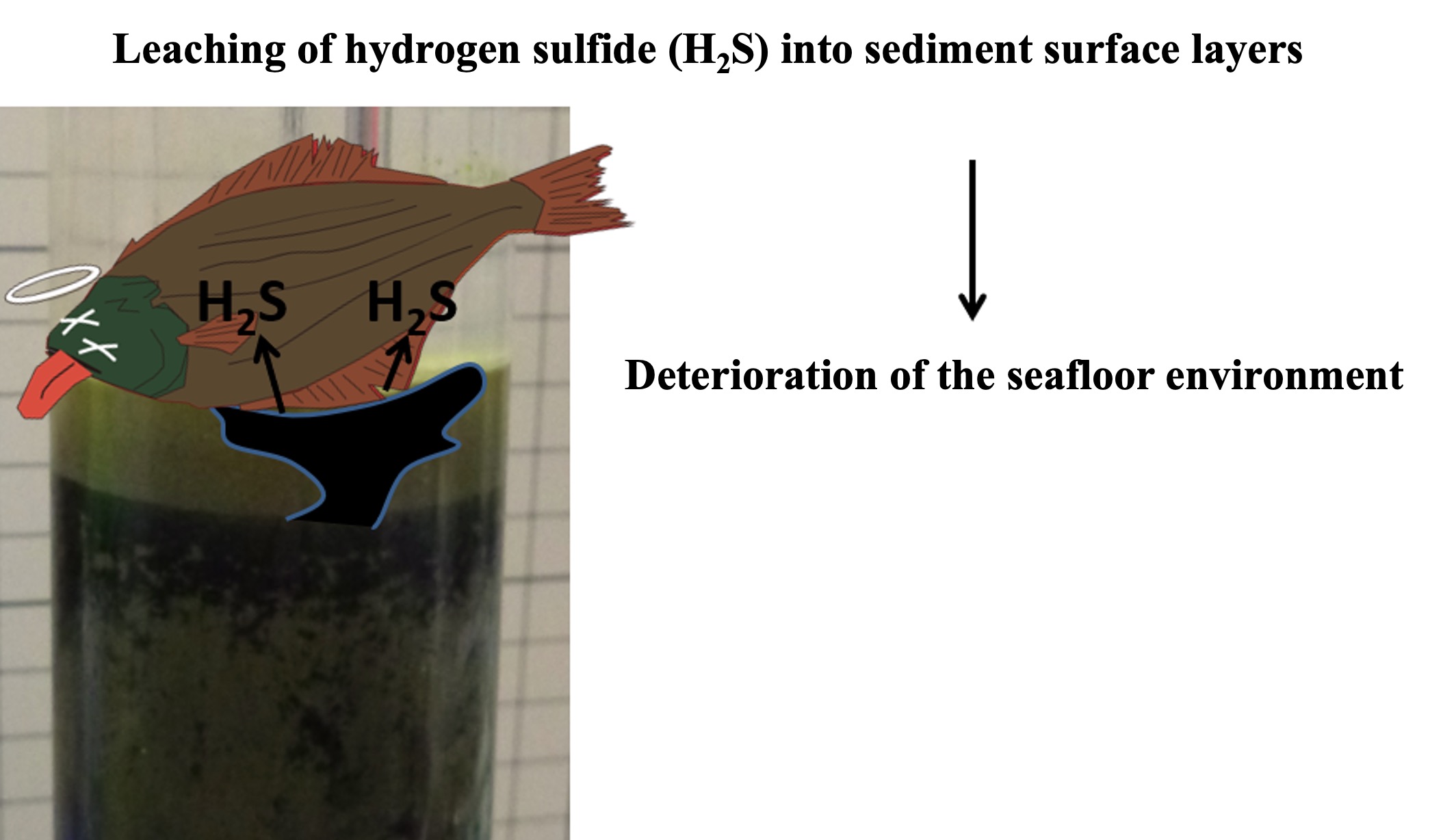

Hydrogen sulfide is highly toxic to many organisms, so exudation of hydrogen sulfide onto sediment surfaces and into bottom waters can be very damaging to ecosystems.