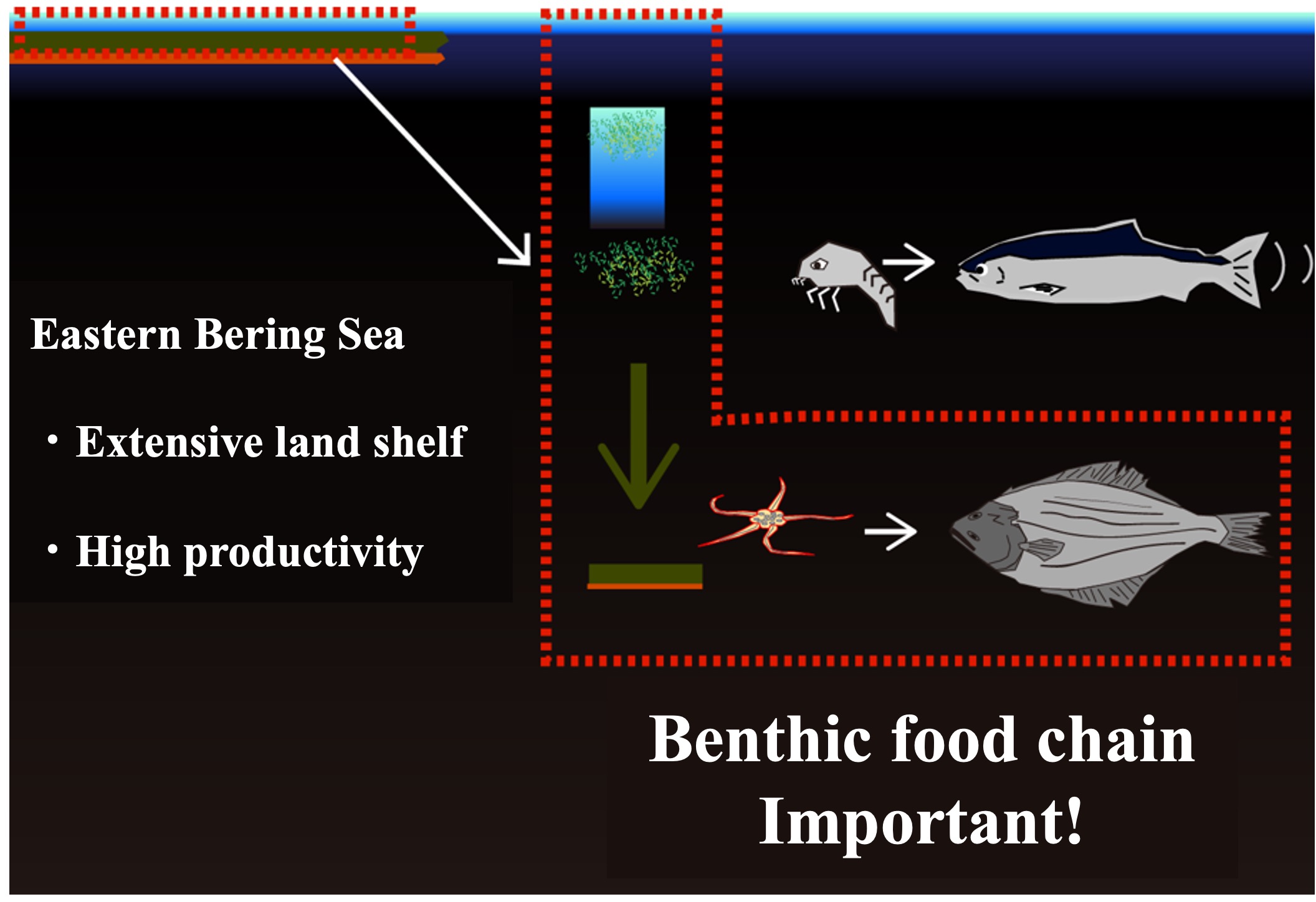

Because the seafloor is covered with organic matter, microscopic animals can easily find food (organic particles). Larger animals gather to feed on these microscopic animals. The seafloor is home to a diverse ecosystem. In the Bering Sea shelf area and the Chukchi Sea, where biological productivity is high, large amounts of organic particles accumulate on the seafloor. Benthos feed on these particles, forming a food chain.

The organisms that make up the seafloor ecosystem are strongly influenced by the seafloor environment and, conversely, play a role in maintaining a favorable seafloor environment

For example, when the anoxic layer in the sediment rises to the surface, it reduces the oxygen concentration of the immediate water and in some cases can bring poisonous hydrogen sulfide into the immediate water. On the other hand, the movement of submersed benthos in the sediment surface layer, or the flounder and flatfish that use their tail fins to scour the bottom sediment, can have the effect of "bioturbating" the sediment, bringing fresh water directly upstream into the sediment. In fact, when the sediments of Funka-Bay are sampled, the amount of benthos is low where there are traces of hydrogen sulfide generation (sulfides), whereas there are no traces of hydrogen sulfide generation where large benthos are sampled. It is likely that the bioturbation of large benthos provides oxygen to the sediments and suppresses the generation of hydrogen sulfide. In Funka-Bay, both of these sites (hydrogen sulfide generation site and habitat of large benthos) seem to be competing with each other in a narrow area. This may be true not only in Funka-Bay, but also in the vast Arctic Ocean shelf area. Working with sediments is an interesting way to capture ocean chemistry in a tangible way and to imagine its relationship with living organisms. I hope that students studying marine resources will also broaden their interest in the seafloor environment by learning about the chemistry of sediments.

Below is an example of benthos taken from a core sample. On the right is a photo of an organism we found polychaetes that had burrowed down to 10 cm below the seafloor during core processing. If something like this shows up in the chemical analysis process, don't be as flustered as he is in the photo. Keep a cool head.