Marine Sediment Dating Methods

In the organic course, we discussed how to use the radiocarbon isotope 14C in seawater carbon (carbonic acid component or organic carbon) to estimate ages. 14C dating can only go back tens of thousands of years at best. To go back tens of thousands to millions of years, other radionuclides must be used.

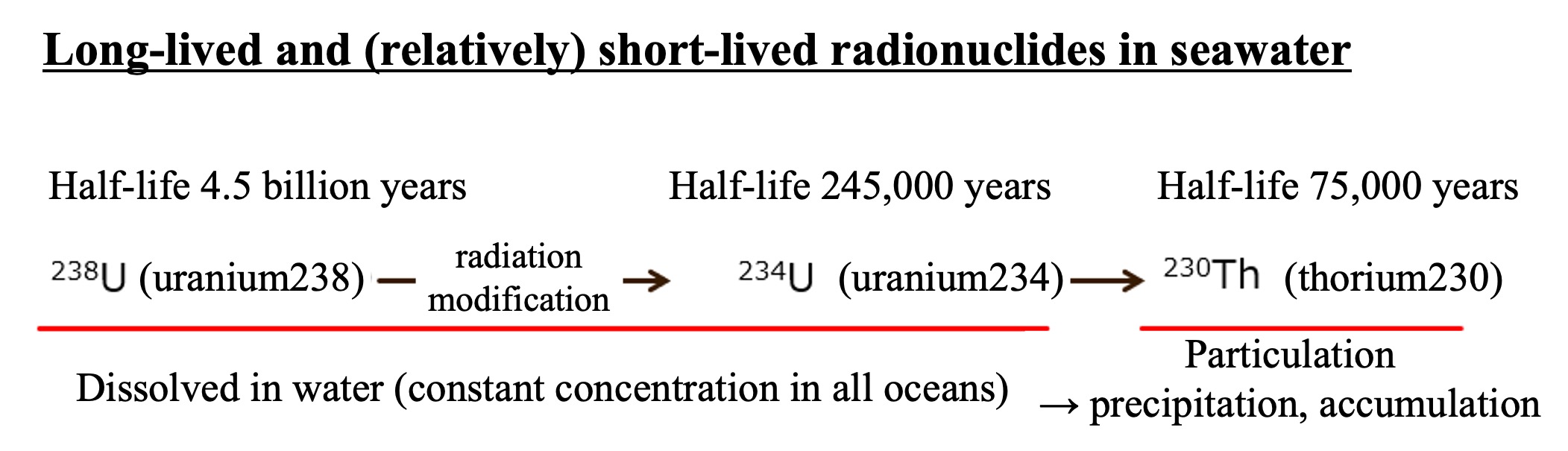

In seawater, 238U (uranium 238), which has a half-life of 4.5 billion years, is dissolved in a certain concentration, and when it undergoes radioactive decay (in the uranium series) starting from 238U, it becomes 234U. 234U undergoes radioactive decay with a half-life of 245,000 years to become 230Th (thorium 230) with a half-life of 75,000 years. Uranium is dissolved in seawater, but thorium instantly becomes particulate, so it tends to precipitate and concentrate on the seafloor by attaching to other settling particles.

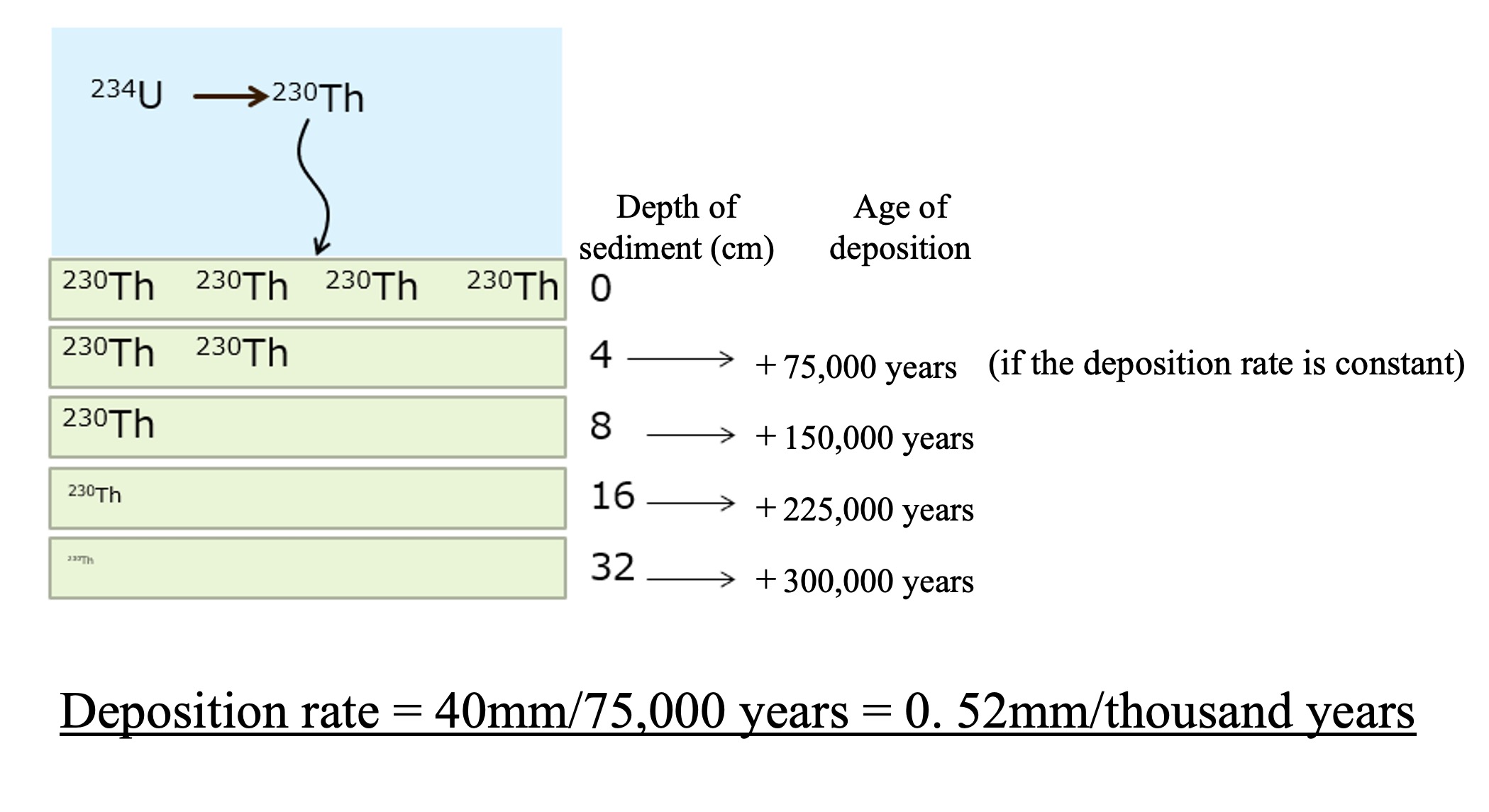

Uranium has been present in seawater at a constant concentration in the past. Therefore, thorium-230 is generated at a constant rate. The thorium-230 generated at a constant rate immediately attaches to the particles in the seawater and is deposited on the seafloor surface along with the settling particles. The particles with attached thorium-230 accumulate on the seafloor surface. The amount of thorium-230 buried in the sediment is reduced to half of its original amount after 75,000 years of radioactive decay. Deeper in the sediments, the proportion of thorium-230 present decreases with time. The ratio of thorium-230 to other radionuclides in the water in the crevices of the sediment (pore water) allows us to calculate the number of years since it was deposited on the seafloor surface.

In the example above, we have shown how the abundance ratio of thorium-230 decreases by half as the sediment deepens by 4 cm. Since the half-life of thorium-230 is 75,000 years, this sedimentation rate is calculated to be 40 mm / 75,000 years = 0.52 mm / thousand years.

It is likely that it is the organic particles that remove thorium-230 from seawater. Most of those organic particles will decompose in the sediment and be gone in a few years. Clay minerals, biogenic opal, and calcium carbonate will remain in the sediment, although they are a small proportion of the settled particles. Thorium-230 does not decompose and will remain as particles in the sediment.

Again, it is important to understand that the sedimentation rate required by this method is the sedimentation rate of particles that remain undecomposed for tens of thousands of years.