Mixed layer change and primary production

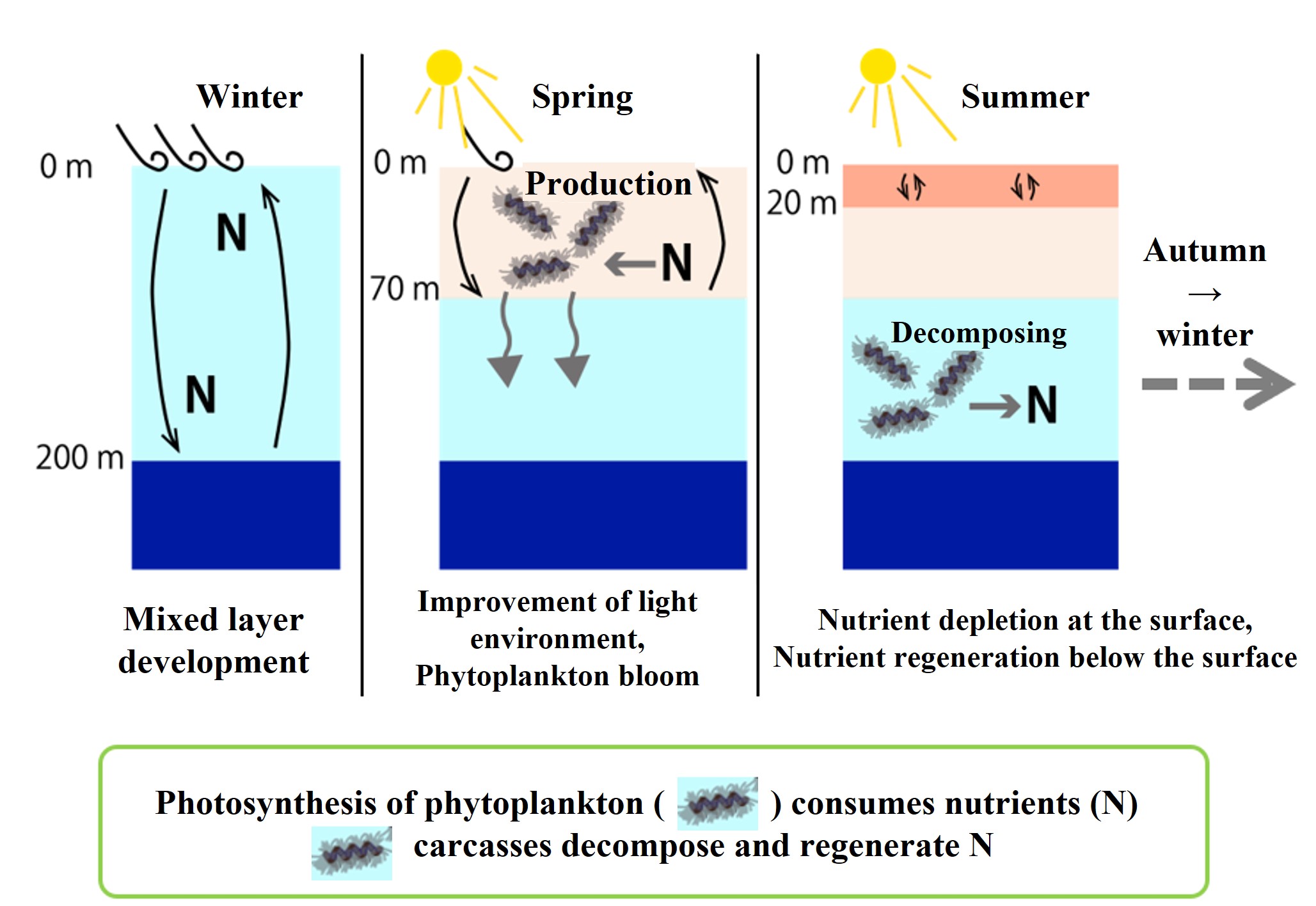

The production of organic matter by plants through photosynthesis is called basic or primary production. In addition to light, carbon dioxide, and water, nutrients are required for primary production. In the ocean, light and nutrient supply determine the spatiotemporal distribution of primary production. The figure below illustrates the relationship between nutrient (N) supply, regeneration, and primary production along with seasonal changes in vertical mixing.

Explanation of the above figure (explained in the order of fall, winter, spring, and summer)

【Autumn → Winter】Nutrients (N) accumulate below the mixed layer (deeper). As the mixed layer depth (200m) deepens in winter, nutrients (N) that have accumulated in deeper areas are taken up within the surface mixed layer. In winter, the water in the mixed layer is in a poor light environment on average because of the weak solar radiation and the movement of water to darker depths within the mixed layer (0 to 200 m). (Even during the day, when the water goes deeper within the mixed layer, it is not exposed to light)

【Winter → Spring】 In spring, the mixed layer becomes thinner (0-70 m) because the winds weaken and solar radiation increases. Furthermore, as the mixed layer becomes thinner, the light environment within the mixed layer becomes better (during the day, the water within the surface mixed layer is constantly exposed to light). The surface mixed layer has sufficient nutrients (N) to allow a large phytoplankton bloom (spring bloom) to occur. During the bloom, nutrients in the surface mixed layer are utilized by primary production. Once the diatom bloom is complete, the diatom population sinks below the mixed layer (sub-surface layer).

【Spring → Summer】 In early summer, the surface mixed layer becomes even shallower, depleting the surface nutrients and inhibiting phytoplankton growth. Even just below the mixed layer, sunlight penetrates and barely any nutrients remain. Photosynthesis occurs just below the mixed layer, and phytoplankton may be found in high densities. This phenomenon can be confirmed by the fact that chlorophyll, the photosynthetic pigment of phytoplankton, shows maximum in the "sub-surface layer" (deeper than the surface mixed layer). This is called the "sub-surface chlorophyll maximum. In most of the sub-surface layer (where little photosynthesis occurs), nutrients are regenerated by the death and decomposition of deposited phytoplankton cells. This is why nutrient concentrations are higher deeper than in the mixed layer.

【Summer → Autumn】 In the autumn, vertical mixing becomes more active due to lower temperatures and weather disturbances. Nutrients are brought to the surface and autumn blooms may be seen.

【Autumn → Winter】 In winter, nutrients accumulated in the sub-surface layer are brought to the surface by vertical mixing.