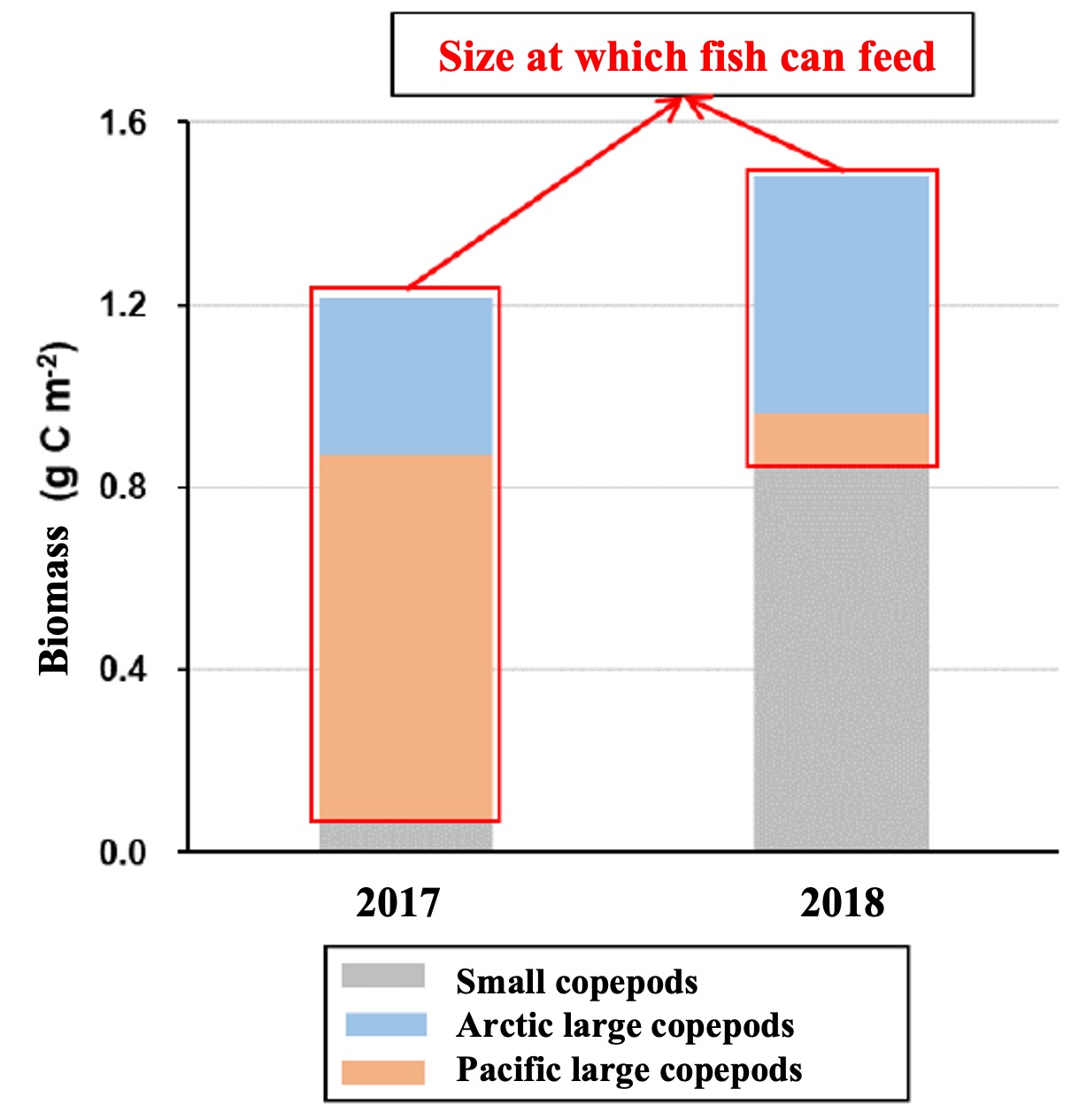

A research group led by Assistant Professor MATSUNO Kohei and Associate Professor YAMAGUCHI Atsushi of the Graduate School of Fisheries Sciences, Hokkaido University has revealed that the proportion of large zooplankton in the northern Bering Sea decreases and the feeding environment for higher predators deteriorates when the sea ice melts early in the season.

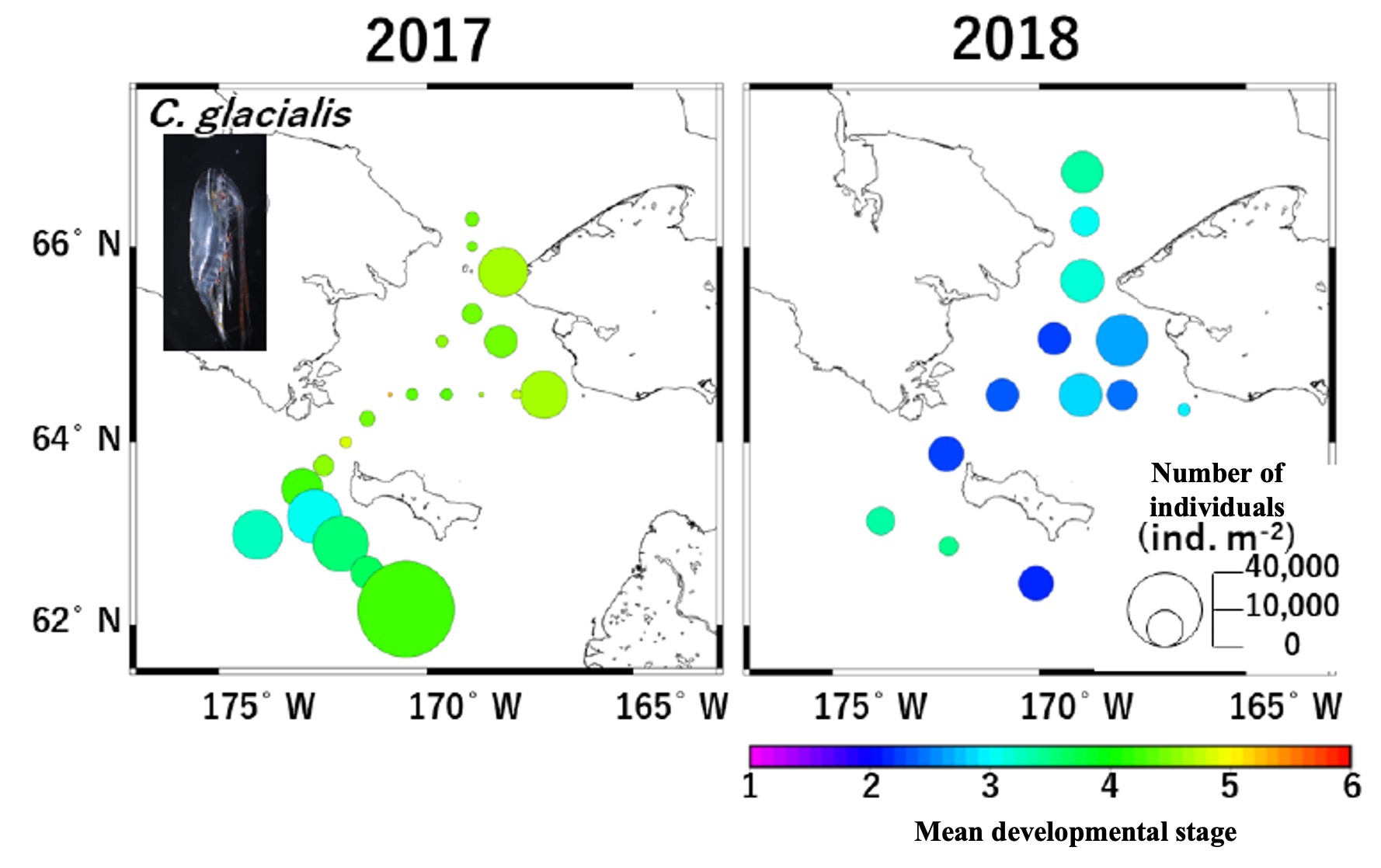

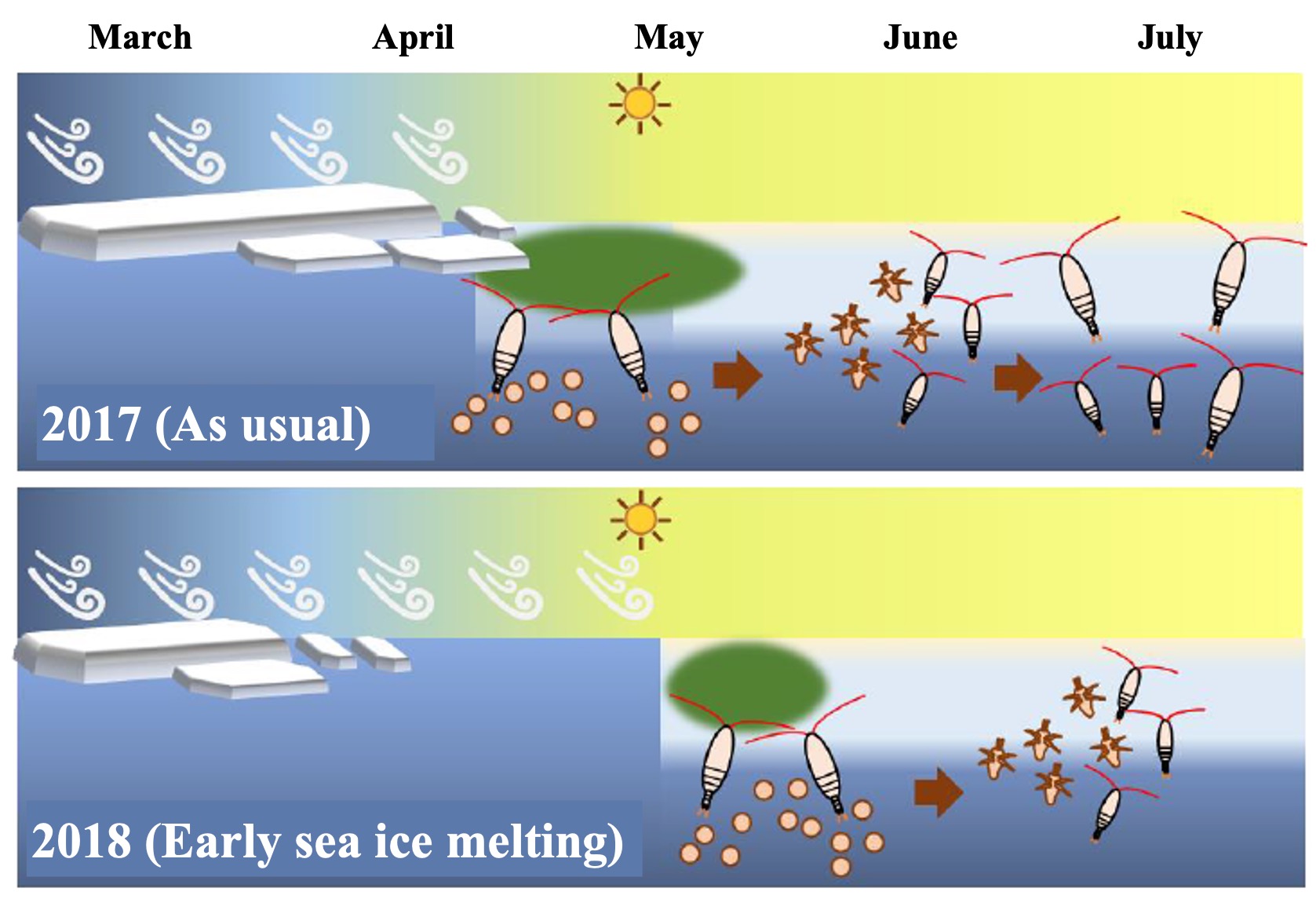

The northern Bering Sea, a continental shelf, is rich in plankton and is one of the world's best fishing grounds for snow crab, king crab, and cod. This sea is usually covered with sea ice from December to April. However, in the spring of 2018, the sea ice melted about one month earlier than usual, which is known to have adversely affected various marine organisms. In particular, decreased populations and worsened nutritional status of higher predators such as fish, seabirds, and pinnipeds were reported, but the cause of the adverse effects of early sea ice melt was still a matter of speculation. The research group conducted oceanographic surveys in the northern Bering Sea in 2017, when sea ice melted as usual, and in 2018, when sea ice melted earlier, and found that early melting of sea ice reduced the amount of large zooplankton useful as food for fish, which in turn reduced the energy received by higher-order predators.

The results of this research clarify one aspect of the process by which climate change modifies marine ecosystems, and will provide valuable knowledge that will greatly contribute to improving the accuracy of future predictions of the changing marine ecosystems.

The results of this research were published in Frontier in Marine Science on Tuesday, February 22, 2022.